Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM)-associated pancreatitis: a case report and a new treatment strategy proposed for PBM

Highlight box

Key findings

• We propose and describe a new treatment strategy for pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM): combining traditional radical surgical program with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to provide useful experiences and references for future treatment of PBM.

What is known and what is new?

• PBM is a rare cause of recurrent pancreatitis. Pancreatobiliary reflux due to PBM is closely associated with a high increased risk of biliary malignancy in such patients. Therefore, the radical surgery occupies an irreplaceable core position in the treatment of PBM. Current clinical practice guidelines for PBM were published in 2012, which recommended the selection of different surgical procedures based on the morphology of the extrahepatic bile ducts.

• ERCP has good therapeutic efficacy and great clinical value for the treatment of PBM. However, this therapeutic advancement has not been summarized in guidelines. We propose a therapeutic strategy combining ERCP with surgery with a view to providing more treatment options for patients with PBM.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• For symptomatic patients with PBM, ERCP is recommended as a transitional treatment before radical surgery to relieve patient discomfort and set the stage for radical surgery.

• For PBM patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation, it is recommended that ERCP be performed as a complementary treatment before cholecystectomy to address reciprocal reflux of the pancreatic fluid and bile.

• For PBM patients who cannot tolerate surgery or refuse to undergo surgery, ERCP may be used as a palliative treatment to reduce the risk of biliary tract malignant to a certain extent.

Introduction

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a rare cause of recurrent pancreatitis (1). Under normal conditions, the sphincter of Oddi encircles the distal common bile duct and pancreatic duct, preventing the free flow of bile and pancreatic fluid (2). In PBM, however, the common bile and pancreatic ducts intersect outside the duodenal wall, which impairs the sphincter control, leading to bi-directional reflux of bile and pancreatic fluid, closely associated with an high increased risk of biliary malignancy (3). In view of the risk of malignant transformation in PBM patients, early selection of appropriate therapeutic strategies would be essential to improve patients’ prognosis.

Herein, we present a typical case of PBM-related recurrent pancreatitis. This case highlights the role of PBM in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis and prompts us to revisit and optimize current therapeutic strategies for PBM. Current clinical practice guidelines for PBM, which are widely referenced in clinical practice, were published in 2012 (4). During the past 10 years, treatment protocols for PBM have been progressively improved and revised; however, the latest therapeutic strategies have not been comprehensively summarized in the literatures. Therefore, we aimed to update management strategies for PBM based on the latest research results to provide clinicians with clearer and more practical therapeutic references. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://tgh.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tgh-24-125/rc).

Case presentation

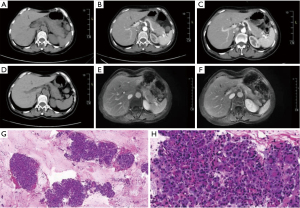

A 59-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain, vomiting and cessation of defecation. The patient had an previous episode of pancreatitis 3 years ago, with no history of other systemic or familial disorders. Physical examination revealed abdominal muscle tension, upper abdominal pain, and diminished bowel sound. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 11.66×109/L (normal range, 4×109/L to 10×109/L), percentage neutrophil level of 88.90% (normal range, 40–75%), blood amylase level of 4,418.2 U/L (normal range, 35–135 U/L), lipase level of 8,518.80 U/L (normal range, 23–300 U/L), D-dimer level of 930.00 ng/mL (normal range, 0–500 ng/mL), and no significant abnormal changes in liver and kidney function, level of electrolytes, or level of female tumor biomarkers. An upper abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan suggested the possibility of pancreatitis (Figure 1A,1B). The treatment approaches used for the patient include dietary restriction, inhibition of gastric acid secretion, inhibition of pancreatic fluid secretion, and rehydration. After 5 days, the patient was relieved of the abdominal pain, and the blood amylase level decreased to 118.8 U/L (normal range, 35–135 U/L) in the follow-up examination. The patient was discharged and scheduled for follow-up in the outpatient clinic.

A month after discharge, the patient’s condition was regularly reviewed in the outpatient clinic. An enhanced CT scan of the upper abdomen was reviewed, and it showed that the pancreas had a fair morphology and density, with a fair peripheral space, and a slightly dilated pancreatic duct (Figure 1C). Six months after discharge, the patient was readmitted to the hospital because of abdominal pain. Physical examination showed epigastric pain, and laboratory tests showed that amylase level was >1,200.0 U/L (normal range, 35–135 U/L), D-dimer level had increased to 1,010 ng/mL (normal range, 0–500 ng/mL), and there were no significant abnormal changes in liver and kidney function, level of electrolytes, immunoglobulin subclass IgG4 assay, extractable nuclear antigen antibody profiles, antinuclear antibody assay, and levels of tumor markers. Upper abdominal CT scan showed pancreatitis [autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) could not be excluded] (Figure 1D). An upper abdominal dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) scan indicated a possibility of AIP (Figure 1E,1F). An ultrasonographic endoscopy was performed to confirm the diagnosis, which showed that the main pancreatic duct exhibited a tortuous course in the biliopancreatic confluence area, with convergence into the lower portion of the common bile duct. The pancreas displayed irregular shape, and the internal echoes were not homogeneous. The tail portion of the pancreatic body was slightly larger, and small patchy hyperechoic echoes were observed. There was no twisting of the pancreatic duct, and no strong echoes were present within it (Video 1). Histopathological ultrasound endoscopy puncture revealed no clear neoplastic lesions, and inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 1G,1H). No malignant tumor cells were found in the punctured pancreatic liquid-based smear, cell block section and the punctured pancreatic cytosmear. The ultrasonographic endoscopic observation of the presence of PBM and the histopathologic findings of the pancreas obtained were the key basis for our diagnosis of PBM, as well as our final exclusion of AIP suggested by upper abdominal CT and upper abdominal dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Considering the patient’s laboratory tests, imaging tests, and ultrasound endoscopy results, we believe that the recurrent pancreatitis experienced by the patient was closely related to PBM and suggest that the patient could undergo endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or surgery. However, the patient refused to undergo ERCP and surgery, was discharged from the hospital after experiencing relief of abdominal pain, and continued to be followed up in the outpatient clinic. The timeline of diagnosis and treatment is listed in Figure 2. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (QYFY WZLL 29918). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Based on the recent progress in PBM management strategies, we systematically summarized and have drawn a flowchart for PBM management (Figure 3). This management strategy combines ERCP, a minimally invasive treatment technique, with surgical procedures based on the morphology of the extrahepatic bile ducts, thereby proposing a revised treatment plan to provide accurate and effective treatment for patients with PBM.

Radical surgery

According to the data obtained from a nationwide statistics conducted in Japan in 1990 (5), among 1,627 patients with PBM, 17.1% suffered from biliary malignant tumors, much higher than the prevalence of biliary malignant tumors in people without PBM. The high risk of biliary malignancy is associated with pancreatic-biliary reflux. Pancreatic duct pressure in the resting state was found to be usually two to three times higher than bile duct pressure (6). Accordingly, in the case with ineffective sphincter muscle control, there is a high tendency for pancreatic fluid to flow into the biliary system along the pressure gradient, while the gallbladder and dilated bile ducts provide sufficient space for the mixing of the refluxed pancreatic fluid and bile. During this process, activated phospholipase A2 in pancreatic fluid hydrolyzes lecithin in bile into lysophosphatidylcholine, a strong cytotoxic agent (7), which leads to repeated injury and repair of the biliary mucosa, followed by hyperplasia and ultimately, the development of malignant tumors (8,9). According to this hypothesis, biliopancreatic diversion should prevent the occurrence of cancer; therefore, choledochoenteric anastomosis was recommended for the treatment of PBM (10,11). However, a significant number of patients still develop bile duct carcinoma after choledochal-intestinal anastomosis (10,12), indicating that other risk factors for biliary tract mucosal malignancy in the absence of pancreatic fluid have not been identified.

An molecular biology-related study has provided an explanation for this phenomenon (13). That is, chronic inflammation of the biliary tract resulting from long-term pancreatic reflux induces the gradual accumulation of gene mutations and the progression of malignant transformation of the biliary epithelial mucosa before the diagnosis of PBM. Therefore, biliopancreatic isolation only cannot reverse the pathological changes that have already occurred. Complete resection of high-grade cancerous sites may be the best curative approach.

Considering that the sites with high incidence of PBM-related biliary malignant tumors vary with the degree of extrahepatic bile duct dilatation, curative options adopted for different types of extrahepatic bile duct dilatation are elaborated to provide patients with effective treatment options.

Radical treatment for PBM-related extrahepatic bile duct dilatation

It is called cystic dilatation when the bile duct diameter is more than twice that of normal bile duct, whereas it is described as coiled or cylindrical dilatation for bile duct with a diameter less than twice the normal bile duct (14). According to a study from Japan (5), biliary tract cancers occurred predominantly in cases of cystic dilatation (63.3%), whereas gallbladder cancers accounted for 36.7% of cases. In contrast, in patients with coiled or cylindrical dilatation, approximately 74.7% of biliary tract cancers occur in the gallbladder, whereas extrahepatic bile duct cancers account for only 25.2%. The incidence of biliary malignancy of these two types is significantly higher than that in the general population, and the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is also greater in patients with extrahepatic bile duct dilatation compared to those without dilatation (5). Therefore, coil or cylindrical cystic dilatation has generally been categorized as combined extrahepatic bile duct dilatation type PBM, and a consensus has been reached on the treatment plan. Once the diagnosis is made, the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts should be resected as early as possible, and biliary reconstructive surgery should be performed (11,15,16).

Radical treatment of PBM without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation

According to a survey in Japan in 1990, approximately 93.2% of biliary tract cancers in PBM without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation occurred in the gallbladder (5). In the second national statistics in Japan, the incidence of gallbladder cancer in these patients reached 37.4% (17). The high risk of gallbladder cancer reflects that the gallbladder is the main site of pancreatic fluid reflux and biliary stasis in these patients. Therefore, the role of prophylactic cholecystectomy in PBM patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation is certain (18).

However, there is no consensus on the management plan for extrahepatic bile ducts. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in PBM patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation was only 3.1% according to a survey in Japan from 2000 to 2007 (17), which was significantly lower than in patients with such dilatation; thus, according to some opinions, the need for prophylactic extrahepatic cholangiopancreatography seems to be insignificant. However, scholars who supported prophylactic resection of the extrahepatic bile ducts pointed out that the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in PBM patients without extrahepatic biliary dilatation was still higher than in the general population (17).

To seek more evidence for the management plan of non-dilated bile ducts, researchers have conducted in-depth studies from histopathological and genetic changes. Hara et al. and Funabiki et al. found that the levels of biliary amylase and the proliferative rate of biliary epithelial cells in non-dilated bile ducts were comparable to those in patients with biliary dilatation with both showing a significant increase (19), and the K-ras mutation rate in the biliary epithelial cells of patients without dilatation was as high as 57% (20). These indicators of high tumorigenic risk support the use of extrahepatic choledochotomy in PBM patients without biliary dilatation. However, Aoki et al. found that in non-dilated bile ducts, biliary sludge was mild, no significant mucosal histopathological alterations were observed, compared with dilated bile ducts, in which the alterations were significantly present. Accordingly, prophylactic extrahepatic choledochotomy might not be necessary in patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation (21).

To understand the practical impact of the different management options for extrahepatic bile ducts on the prognosis of these patients, clinicians have conducted follow-ups of patients who underwent surgical treatment, and the relevant reports (21-33) are presented in Table 1. The preservation of extrahepatic bile does not significantly increase the risk of cholangiocarcinoma based on the limited clinical studies available; therefore, most clinicians prefer to perform simple cholecystectomy in patients who do not have preoperative symptoms. In two national surveys conducted in Japan from 1990 to 1999 and from 2000 to 2007, the proportion of adult PBM patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation who underwent combined extrahepatic bile ducts resection declined from 45% to 29.8% (5). PBM-related guidelines published in 2013 also recommended cholecystectomy alone with extrahepatic bile duct preservation in such patients (4,17). Notably, the management strategy for patients with symptoms should be different from that for asymptomatic patients, and it is recommended that extrahepatic bile ducts be removed when cholecystectomy is performed to prevent recurrent symptoms triggered by incomplete pancreaticobiliary reflux blockage (34).

Table 1

| Author | Publication year | No. of cases | Age (years)* | Clinical presentation | Surgical procedure (n/N) | Follow-up (years)* | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aoki et al. (21) | 2001 | 8 | 49.2±11.1 | Asymptomatic | Cholecystectomy (8/8) | 2.8–16.3 | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

| Okada et al. (22) | 1981 | 1 | 7 | Abdominal pain, jaundice, nausea, vomiting | Cholecystectomy + common bile duct excision + hepaticojejunostomy (1/1) | 1.5 | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

| Ando et al. (23) | 1995 | 7 | 3.3 (1–6) | Recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, and bile-stained stools | Cholecystectomy + common bile duct excision + hepaticojejunostomy (7/7) | 1–7 | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

| Sugiyama et al. (24) | 1998 | 8 | Not available | Asymptomatic | Cholecystectomy (8/8) | 4.7 (0.6–7) | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

| Sugiyama et al. (25) | 1999 | 11 | Not available | Asymptomatic | Cholecystectomy (11/11) | 6.7 | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

| Kusano et al. (26) | 2002 | 18 | 54.8 | Asymptomatic | Cholecystectomy (18/18) | 1.7–17.4 | Three patients died of other diseases; the remaining 15 patients survived without symptoms and malignant tumors |

| Shimotakahara et al. (27) | 2003 | 17 | 2.9 | Asymptomatic | Hepaticojejunostomy (14/17), hepaticoduodenostomy (3/17) | 9.8 | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

| Tsuchida et al. (28) | 2004 | 14 | 52.4 (27–79) | Five cases were already diagnosed with gallbladder cancer | Cholecystectomy (14/14) | 8.3 (1.4–18.8) | One patient died from recurrence of gallbladder cancer; the remaining 13 patients survived without symptoms or malignant tumors |

| Kusano et al. (29) | 2005 | 29 | 47.3 (3–76) | Not available | Cholecystectomy (29/29) | 13.4 (3–27.2) | One patient died from gastric cancer, and two patients died from other diseases; the remaining 26 patients survived without symptoms or malignant tumors |

| Ohuchida et al. (30) | 2006 | 19 | Not available | Abdominal pain, back pain, jaundice | Cholecystectomy (14/19), cholecystectomy + hepatic bile duct resection + hepaticojejunostomy (2/19), cholecystectomy + common bile duct stone removal (1/19), cholecystectomy + duodenectomy (1/19), cholecystectomy + common bile duct stone removal + hepatectomy (1/19) | 9.3±4.7 | Two patients died from other diseases; the remaining 17 patients survived without symptoms or malignant tumors |

| Yamada et al. (31) | 2013 | 1 | 75 | Gallbladder cancer | Cholecystectomy (1/1) | 20 | Bile duct cancer occurred during follow-up |

| Miyake et al. (32) | 2022 | 7 | 4.2 (1–8) | Abdominal pain, elevated serum amylase levels, vomiting, jaundice | Hepatic bile duct resection + hepaticojejunostomy (7/7) | 17.6 (6–28) | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

| Liu et al. (33) | 2022 | 10 | 3 (1–9) | Abdominal pain, jaundice, recurrent pancreatitis | Cholecystectomy + choledochectomy + hepaticojejunostomy (10/10) | 1.1–4.5 | Asymptomatic, no malignant tumors |

*, because different literatures have different ways of counting age and follow-up time, we use any of the following four ways to express time, including mean (e.g., 54.8), mean ± SD (e.g., 49.2±11.1), range (e.g., 2.8–16.3) or mean (range) [e.g., 3.3 (1–6)]. PBM, pancreaticobiliary maljunction; SD, standard deviation.

However, these clinical studies were all short to medium-term follow-ups with small sample sizes, making it difficult to fully capture the long-term prognostic effects of cholecystectomy alone. It is necessary to expand the sample size for lifelong follow-up studies and conduct randomized controlled trials to clarify the necessity of extrahepatic cholecystectomy.

ERCP treatment

Surgery as a radical treatment for patients with PBM has significant therapeutic effects. However, a considerable number of PBM patients are hospitalized due to abdominal pain, jaundice, fever and other symptoms, which are usually associated with biliary tract and pancreatic inflammation. It is necessary to adopt transitional therapeutic measures to alleviate patient discomfort and simultaneously reduce the risk of postoperative complications.

The idea that PBM-associated cholangitis is closely related to the irritation of the biliary mucosa due to pancreatic reflux is widely recognized. However, the establishment of animal models of pancreatitis supported that the obstruction of the pancreatic effluent outflow tract plays a much more critical role in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis (35) than biliary reflux into the pancreatic duct (36) under specific circumstances where the biliary pressure may temporarily increase such as postprandial gallbladder contraction (37), which explains why pancreatitis may still occur in some patients who underwent extrahepatic choledochotomy with biliary tract reconstruction. There are two distinctive features of the pancreatic outflow tract in symptomatic patients with PBM, one of which is that obstructions, such as stones or proteinaceous plugs, are often present in the distal pancreaticobiliary ducts or the common channels of these patients (23,25,38-40). These pancreatic fluids and cholestatic products can significantly elevate the pressure in the pancreatic outflow tract, which in turn triggers pancreatic fluid stasis. In addition, measurements of the sphincter of Oddi pressure showed that the basal and peak contraction pressures were significantly higher in symptomatic PBM patients compared to those without PBM (41-44), suggesting that spasm of the sphincter of Oddi is a significant factor contributing to biliopancreatic outflow obstruction in patients with PBM. Based on the above phenomena, the key to solving PBM-associated cholangitis and pancreatitis is to relieve the obstruction of the pancreaticobiliary outflow tract, ensuring a smooth and unobstructed flow of bile and pancreatic fluid.

Recently, ERCP has harnessed its strengths in relieving symptoms associated with PBM, and the relevant literature has been systematically organized in Table 2 (44-56). Since the length of functional sphincter segments in patients with PBM is not different from that of the general population, endoscopic sphincterotomy can be used to completely incise the spastic sphincter in patients with PBM (43), which helps reduce the pressure of pancreaticobiliary outflow tracts and helps pancreatic fluid and bile flow smoothly into the duodenum along the pressure gradient, thus significantly reducing or even eliminating the risk of pancreaticobiliary reciprocal reflux. In addition, ERCP can effectively remove obstructions, such as stones and protein plugs, in the pancreaticobiliary outflow tract and ensure smooth drainage of pancreatic and biliary juices through indwelling stents or catheters when necessary. Several studies have shown that the effectiveness of ERCP ranges from 45.4% to 87%, and the complication rate is relatively low. ERCP is now widely recommended in the literature as the first step in treating symptomatic patients with PBM (57,58).

Table 2

| Author | Publication year | No. of cases | Age (years)* | Morphological characteristics of pancreaticobiliary duct | Clinical presentation | ERCP procedure (n/N) | Follow-up time | ERCP efficacy rate | Repeat ERCP | Additional surgical procedure | Incidence of carcinogenesis during follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guelrud et al. (44) | 1999 | 9 | 7.8 (2.9–17) | 7 patients with extrahepatic bile duct dilation, while 2 patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Recurrent acute pancreatitis | EST (9/9), ERPD (5/9) | Average of 26.4 months (ranging from 18 to 38 months) | 8 patients remained asymptomatic, while 1 patient continued to experience abdominal pain but did not have a recurrence of pancreatitis | None | None | None |

| Ng et al. (45) | 1992 | 6 | 1.8–10 | Mild CBD dilatation (CBD diameter <15 mm) with a common channel length less than 15 mm | Abdominal pain, elevated serum amylase, fever, obstructive jaundice, recurrent pancreatitis | 6 patients underwent a total of 8 EST | Average of 4 years (ranging from 1.5 to 6.5 years) | 5 patients did not experience symptoms after ERCP | 2 patients underwent additional ERCP | 1 patient underwent extrahepatic bile duct resection and hepaticojejunostomy | None |

| Jaunin-Stalder et al. (46) | 2002 | 2 | 7 | With extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Acute pancreatitis, acute cholangitis | EST (2/2) | Follow-up was conducted at 12 months and 9 months, respectively | Both 2 patients experienced symptom relief, occasional abdominal pain, and no recurrence of pancreatitis or cholangitis | None | None | None |

| Eyben et al. (47) | 2007 | 1 | 20 | Without extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Acute pancreatitis | EST | 6 months | No more abdominal pain | None | Cholecystectomy performed immediately after ERCP | None |

| Terui et al. (48) | 2008 | 4 | 1–7 | Not available | Intractable acute pancreatitis | EST | 2–10 years | Symptoms significantly improved in all 4 cases | None | Cholecystectomy and choledochoduodenostomy performed in all 4 cases to reduce the risk of carcinogenesis | None |

| Jin et al. (49) | 2017 | 63 | 24 (1–82) | 29 patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice, fever | A total of 74 ERCP treatments were administered to 63 patients, pre-cut (1/74), EST (57/74), EHP (4/74), EPBD (11/74), stricture dilation (5/74), stone extraction (46/74), ERBD (15/74), ERPD (4/74), ENBD (48/74), ENPD (3/74) | Average of 27 months (ranging from 14 days to 82 months) | The overall effective rate was 60.7%, with a significant decrease in the severity and frequency of abdominal pain | 10 patients underwent repeat ERCP | 12 patients underwent radical surgery | 2 patients developed gallbladder cancer |

| Zeng et al. (50) | 2019 | 75 | 6 (0.75–16) | 46 patients with extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice, fever, acute pancreatitis, bilious stools, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated transaminases | A total of 112 ERCP treatments were administered to 75 patients, EPS (19/75), EST (42/75), ERPD (8/75), ERBD (17/75), ENBD (33/75), EPBD (2/75), ENPD (3/75), stone extraction (40/75), bougienage (5/75) | Average of 46 months (ranging from 2 to 134 months) | The overall effective rate was 82.4%, with significant relief of symptoms | 5 patients underwent repeat ERCP due to recurrent pancreatitis | 11 patients underwent extrahepatic duct resection with jejunal anastomosis due to recurrent pancreatitis or concerns about the risk of carcinogenesis | None |

| Wang et al. (51) | 2020 | 24 | 3.8 | Mild dilation of CBD (CBD diameter <10 mm) | Not available | EST (21/24), ENBD (24/24), stone extration (18/24) | All patients underwent immediate surgical treatment | A significant decrease in perioperative parameters and postoperative complications | None | All surgeries involved hepatic duct resection followed by hepaticojejunostomy | None |

| Zhang et al. (52) | 2022 | 90 | 5.5±5.5 | 74 patients with extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, jaundice, malaise | A total of 127 ERCP treatments were administered to 90 patients, biliary stone extraction (65/127), EST (57/127), ERBD (48/127), ENBD (41/127), bougienage (5/127), balloon dilation (2/127), EPS (20/127), ERPD (14/127), ENPD (5/127), pancreatic duct dilation (7/127), pancreatic duct stone extraction (18/127) | 6 months | Improvement was observed in 80 patients (88.9%), with 68 patients (75.6%) showing improvement after the first ERCP procedure | 12 patients (13.3%) showed improvement after the second ERCP procedure | 15 patients underwent definitive surgery due to recurrent symptoms or concerns about the risk of malignancy | None |

| Qian et al. (53) | 2024 | 33 | 5.7 (1.5–12.1) | Without extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice, fever | EST (33/33), stone extraction (27/33), ENBD (16/33), ERPD (15/33), EPBD (12/33), ERBD (3/33) | 12 to 24 months | 45.4% of patients were successfully treated with ERCP and remained asymptomatic | 15.1% of patients required repeat ERCP | 30.3% eventually underwent additional surgical interventions | None |

| Sundaram et al. (54) | 2023 | 5 | 11 (4–25) | 1 patient with extrahepatic bile duct dilation, the remaining 4 patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilation | Recurrent acute pancreatitis (2 cases), chronic pancreatitis (3 cases) | EST + ERPD (5/5) | 6 months | Patients with recurrent pancreatitis did not experience further episodes of pancreatitis. Patients with chronic pancreatitis reported a reduction in pain scores | None | None | None |

| Ariga et al. (55) | 2024 | 1 | 70 | Not available | Recurrent acute pancreatitis | EPBD | 2 months | Not available | None | Cholecystectomy, hepatic duct resection, and hepaticojejunostomy were performed 2 months after ERCP | None |

| Samavedy et al. (56) | 1999 | 15 | 36 (6–76) | 7 patients with extrahepatic bile ducts dilation, the remaining 9 patients without extrahepatic bile ducts dilation | Pancreatitis, abdominal pain, jaundice | EST (14/15), ERBD (5/15) | Average of 32 months | 9 patients did not experience pancreatitis or abdominal pain recurrence, while in 4 cases, the recurrence frequency decreased. Two patients did not show improvement in symptoms | 2 patients underwent repeat ERCP due to recurrent pancreatitis | 1 patient underwent extrahepatic bile duct resection due to persistent symptoms | None |

*, because different literatures have different ways of counting age, we use any of the following four ways to express time, including mean (e.g., 7), mean ± SD (e.g., 5.5±5.5), range (e.g., 1.8–10) or mean (range) [e.g., 7.8 (2.9–17)]. CBD, common bile duct; EHP, endoscopic hemoclip placement; ENBD, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; ENPD, endoscopic nasopancreatic drainage; EPBD, endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation; ERBD, endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ERPD, endoscopic retrograde pancreatic drainage; EPS, endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy; EST, endoscopic sphincterotomy; PBM, pancreaticobiliary maljunction; SD, standard deviation.

However, the efficacy of ERCP is closely related to the diameter of the bile duct (53). Pancreatitis recurred in two children with PBM and dilated bile ducts who underwent ERCP for pancreatitis. In contrast, in patients without biliary dilatation, there was no recurrence of pancreatitis within 2 years of ERCP (59). Samavedy et al. (56) also found that in one of six pancreatitis patients with extrahepatic bile duct dilatation, symptoms persisted after undergoing endoscopic-sphincterotomy (EST), whereas in the other six pancreatitis patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation, symptoms completely disappeared or significantly reduced after EST. To accurately determine which patients are more suitable for ERCP, we need to accumulate a large amount of clinical evidence to clarify the morphologic characteristics of the pancreatic bile ducts that are suitable for ERCP.

Indeed, pancreaticobiliary outflow tract obstruction leading to reciprocal reflux of the pancreatic fluid and bile is often neglected in current radical surgical procedures of patients without biliary dilatation, and cholecystectomy alone cannot completely resolve pancreaticobiliary reciprocal reflux. Intraoperative manometry by Imazu et al. demonstrated that sphincter of Oddi pressures were higher in patients with high levels of biliary amylase than low levels of biliary amylase (60), which revealed a strong link between increased sphincter of Oddi pressures and increased pancreatic fluid reflux. Given the effectiveness of ERCP in relieving sphincter of Oddi spasm, we suggest that ERCP should be performed as a complementary treatment before cholecystectomy for PBM patients without extrahepatic bile duct dilatation to achieve a comprehensive and effective treatment.

For patients with undesirable outcomes following ERCP, extrahepatic choledochotomy is recommended to avoid the physiological and psychological burdens of unnecessary multiple invasive operations. Qian et al. conducted a study comparing the efficacy of ERCP with that of surgery for treating of children with PBM (53) and found that the therapeutic efficacy of ERCP was still insufficient compared with that of surgery. Therefore, radical surgery remains the best treatment option for eligible PBM patients. However, in some patients with poor underlying conditions who cannot tolerate surgery or refuse to undergo surgery, ERCP may be used as a palliative treatment to reduce the risk of biliary tract malignant caused by pancreaticobiliary reflux to a certain extent.

This case report provides a typical case of PBM-associated pancreatitis. Given the necessity of PBM treatment, we review the radical surgical options for PBM and summarize recent advances in ERCP. In the course of diagnosing and treating this case, we found that there was a possibility of misdiagnosis of PBM-associated pancreatitis as AIP. At the patient’s second admission for acute pancreatitis, CT and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of the upper abdomen suggested the possibility of AIP. AIP is a specific type of chronic pancreatitis with nonspecific symptoms such as obstructive jaundice and abdominal discomfort as the main clinical manifestations. Patients with AIP often have elevated serum IgG4 levels, which can be used as the laboratory test for diagnosing, evaluating the efficacy of treatment, and monitoring the activity of the disease. AIP is characterized by diffuse enlargement of the pancreas with peripancreatic peripheral rims on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT and MR, which is a more specific imaging manifestation of AIP. Ultrasound endoscopy can detect the pancreatic parenchymal and pancreaticobiliary changes characteristic of AIP, and can obtain histologic or cytologic specimens to aid in the diagnosis, making it an important diagnostic method for AIP. Unlike the common features of AIP, our patient had abdominal pain as the main manifestation, no jaundice, no elevation of indicators related to biliary obstruction, and no elevation of IgG4. To further clarify the diagnosis, we performed ultrasonographic endoscopy and obtained histologic and cytologic specimens. Ultrasonographic endoscopy showed the presence of PBM and did not reveal the pancreatic parenchymal and pancreaticobiliary ductal changes characteristic of AIP, and the histology and cytology did not support the diagnosis of AIP, which was the most important basis for us to rule out AIP and confirm the diagnosis of PBM. In view of the fact that some patients with PBM may be difficult to distinguish from AIP by imaging alone, we strongly recommend that ultrasonographic endoscopy be performed and pancreatic histologic and cytologic specimens be obtained in these patients to provide the most reliable basis for the diagnosis from a pathological point of view.

Given the critical role of radical surgery and ERCP in the treatment of PBM, we actively recommended that the patient receive these treatments. Unfortunately, the patient refused radical surgery or ERCP treatment, which led to two lack of rigor in our case. From the perspective of disease diagnosis, the lack of ERCP prevented us from testing the patient’s biliary amylase level, which somewhat compromised our diagnostic rigor. Since pancreatic duct pressure is usually higher than bile duct pressure, reflux of pancreatic fluid into the bile duct is often present in patients with PBM. Elevated biliary amylase level is a strong evidence reflecting pancreaticobiliary reflux, which can be used as an important auxiliary diagnostic basis for PBM. In our future clinical work, we will actively recommend biliary amylase measurement in PBM patients undergoing ERCP to help more accurate diagnosis. In addition, the lack of radical surgery or ERCP treatment may severely affect the prognosis of patients, resulting in recurrent episodes of PBM-associated pancreatitis, and potentially the development of biliary tract malignancies.The occurrence of PBM-associated pancreatitis may be related to the sphincter of Oddi spasm or the presence of proteinaceous plugs or stones obstructing the pancreatic fluid outflow tract. Combined with the patient’s history of three episodes of acute pancreatitis, we had a high suspicion that the patient may have had spasticity of the sphincter of Oddi or intermittent obstruction of the pancreatic fluid outflow tract by proteinaceous plugs. However, due to the patient’s refusal of ERCP and surgical treatment, we were unable to confirm and resolve this problem, which could have led to the recurrence of pancreatitis. In addition, the biliary mucosal damage caused by long-term pancreatobiliary reflux is an important cause of the high incidence of biliary malignant tumors, and statistically, patients with PBM between the ages of 50–65 years old are most likely to suffer from biliary malignant tumors. are most likely to suffer from biliary malignant tumors (4). Based on the high risk of acute pancreatitis and tumors, we will continue to follow this patient and advise her to receive active treatment to minimize the impact of disease recurrence and progression on the patient’s quality of life.

Conclusions

After exploring the research progress on PBM, we realized that radical surgery still occupies an irreplaceable core position in the treatment of PBM. At the same time, the new therapeutic value of ERCP in treating PBM patients should not be ignored, as this minimally invasive technique combined with radical surgery has shown beneficial efficacy in many studies. We believe that it is necessary to incorporate ERCP transitional treatment into PBM management guidelines to establish a complete clinical management strategy for PBM. In addition, ERCP has shown potential clinical value in complementary and palliative treatment in patients with uncomplicated extrahepatic biliary dilatation PBM and those who do not need subsequent surgical interventions and may be expected to become a new hotspot for future research on PBM management strategies. We expect that through further research and clinical practice, the advantages of ERCP in the treatment of PBM will be fully utilized to compensate for the shortcomings of radical surgical procedures and provide patients with more minimally invasive and highly effective treatment options to maximize their quality of life.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language polishing.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://tgh.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tgh-24-125/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tgh.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tgh-24-125/prf

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tgh.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tgh-24-125/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (QYFY WZLL 29918). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rho ES, Kim E, Koh H, et al. Two cases of chronic pancreatitis associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union and SPINK1 mutation. Korean J Pediatr 2013;56:227-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suda K, Miyano T, Hashimoto K. The choledocho-pancreatico-ductal junction in infantile obstructive jaundice diseases. Acta Pathol Jpn 1980;30:187-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Anjiki H, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:S84-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamisawa T, Ando H, Suyama M, et al. Japanese clinical practice guidelines for pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Gastroenterol 2012;47:731-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tashiro S, Imaizumi T, Ohkawa H, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2003;10:345-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Csendes A, Kruse A, Funch-Jensen P, et al. Pressure measurements in the biliary and pancreatic duct systems in controls and in patients with gallstones, previous cholecystectomy, or common bile duct stones. Gastroenterology 1979;77:1203-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neiderhiser DH, Morningstar WA, Roth HP. Absorption of lecithin and lysolecithin by the gallbladder. J Lab Clin Med 1973;82:891-7. [PubMed]

- Shimada K, Yanagisawa J, Nakayama F. Increased lysophosphatidylcholine and pancreatic enzyme content in bile of patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction. Hepatology 1991;13:438-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuge S. Experimental studies on anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system in puppies with a pancreaticocholedochal end-to-side anastomosis. Tokushima J Exp Med 1984;31:67-78. [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya R, Harada N, Ito T, et al. Malignant tumors in choledochal cysts. Ann Surg 1977;186:22-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones AW, Shreeve DR. Congenital dilatation of intrahepatic biliary ducts with cholangiocarcinoma. Br Med J 1970;2:277-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, et al. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg 1977;134:263-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuchida A, Itoi T, Aoki T, et al. Carcinogenetic process in gallbladder mucosa with pancreaticobiliary maljunction Oncol Rep 2003;10:1693-9. (Review). [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cazares J, Koga H, Yamataka A. Choledochal cyst. Pediatr Surg Int 2023;39:209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi S, Asano T, Yamasaki M, et al. Prophylactic excision of the gallbladder and bile duct for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Arch Surg 2001;136:759-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swisher SG, Cates JA, Hunt KK, et al. Pancreatitis associated with adult choledochal cysts. Pancreas 1994;9:633-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morine Y, Shimada M, Takamatsu H, et al. Clinical features of pancreaticobiliary maljunction: update analysis of 2nd Japan-nationwide survey. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013;20:472-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi S, Koga A, Matsumoto S, et al. Anomalous junction of pancreaticobiliary duct without congenital choledochal cyst: a possible risk factor for gallbladder cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 1987;82:20-4. [PubMed]

- Hara H, Morita S, Ishibashi T, et al. Surgical treatment for non-dilated biliary tract with pancreaticobiliary maljunction should include excision of the extrahepatic bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:984-7. [PubMed]

- Funabiki T, Matsubara T, Miyakawa S, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009;394:159-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoki T, Tsuchida A, Kasuya K, et al. Is preventive resection of the extrahepatic bile duct necessary in cases of pancreaticobiliary maljunction without dilatation of the bile duct? Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001;31:107-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okada A, Nagaoka M, Kamata S, et al. “Common channel syndrome”--anomalous junction of the pancreatico-biliary ductal system. Z Kinderchir 1981;32:144-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ando H, Ito T, Nagaya M, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction without choledochal cysts in infants and children: clinical features and surgical therapy. J Pediatr Surg 1995;30:1658-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction without congenital choledochal cyst. Br J Surg 1998;85:911-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Kuroda A. Pancreatic disorders associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction. Surgery 1999;126:492-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kusano T, Isa T, Tsukasa K, et al. Long-term results after cholecystectomy alone for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation. Int Surg 2002;87:107-13. [PubMed]

- Shimotakahara A, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, et al. Forme fruste choledochal cyst: long-term follow-up with special reference to surgical technique. J Pediatr Surg 2003;38:1833-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuchida A, Itoi T, Endo M, et al. Pathological features and surgical outcome of pancreaticobiliary maljunction without dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct. Oncol Rep 2004;11:269-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kusano T, Takao T, Tachibana K, et al. Whether or not prophylactic excision of the extrahepatic bile duct is appropriate for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation. Hepatogastroenterology 2005;52:1649-53. [PubMed]

- Ohuchida J, Chijiiwa K, Hiyoshi M, et al. Long-term results of treatment for pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation. Arch Surg 2006;141:1066-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamada S, Shimada M, Utsunomiya T, et al. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma accompanied by pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation 20 years after cholecystectomy: report of a case. J Med Invest 2013;60:169-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyake H, Fukumoto K, Yamoto M, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction without biliary dilatation in pediatric patients. Surg Today 2022;52:207-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu F, Lan M, Xu X, et al. Application of Embedding Hepaticojejunostomy in Children with Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction Without Biliary Dilatation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2022;32:336-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Surgical strategy for patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction without choledochal cyst. Int Surg 1995;80:215-7. [PubMed]

- Lerch MM, Saluja AK, Rünzi M, et al. Pancreatic duct obstruction triggers acute necrotizing pancreatitis in the opossum. Gastroenterology 1993;104:853-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raffensperger JG, Given GZ, Warrner RA. Fusiform dilatation of the common bile duct with pancreatitis. J Pediatr Surg 1973;8:907-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura T, Okada A, Higaki J, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction-associated pancreatitis: an experimental study on the activation of pancreatic phospholipase A2. World J Surg 1996;20:543-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oh C, Cheun JH, Kim HY. Clinical comparison between the presence and absence of protein plugs in pediatric choledochal cysts: experience in 390 patients over 30 years in a single center. Ann Surg Treat Res 2021;101:306-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weng M, Wang L, Weng H, et al. Utility of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in infant patients with conservational endoscopy. Transl Pediatr 2021;10:2506-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaneko K, Ando H, Ito T, et al. Protein plugs cause symptoms in patients with choledochal cysts. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:1018-21. [PubMed]

- Sai JK, Ariyama J, Suyama M, et al. Occult regurgitation of pancreatic juice into the biliary tract: diagnosis with secretin injection magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:929-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beltrán MA. Current knowledge on pancreaticobiliary reflux in normal pancreaticobiliary junction. Int J Surg 2012;10:190-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto S, Tanaka M, Ikeda S, et al. Sphincter of Oddi motor activity in patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:831-4. [PubMed]

- Guelrud M, Morera C, Rodriguez M, et al. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in children with recurrent pancreatitis and anomalous pancreaticobiliary union: an etiologic concept. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:194-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng WD, Liu K, Wong MK, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in young patients with choledochal dilatation and a long common channel: a preliminary report. Br J Surg 1992;79:550-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaunin-Stalder N, Stähelin-Massik J, Knuchel J, et al. A pair of monozygotic twins with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction and pancreatitis. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:1485-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eyben A, Aerts R, Verslype C. Young female with pancreaticobiliary maljunction presenting with acute pancreatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2007;70:363-6. [PubMed]

- Terui K, Yoshida H, Kouchi K, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy is a useful preoperative management for refractory pancreatitis associated with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Pediatr Surg 2008;43:495-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jin Z, Bie LK, Tang YP, et al. Endoscopic therapy for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction: a follow-up study. Oncotarget 2017;8:44860-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng JQ, Deng ZH, Yang KH, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in children with symptomatic pancreaticobiliary maljunction: A retrospective multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol 2019;25:6107-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Moon SB, Zang J, et al. Usefulness of pre-operative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in diagnosis and management of forme fruste choledochal cyst in children. ANZ J Surg 2020;90:1041-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang JY, Deng ZH, Gong B. Clinical characteristics and endoscopic treatment of pancreatitis caused by pancreaticobiliary malformation in Chinese children. J Dig Dis 2022;23:651-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qian M, Wang J, Sun S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Children of Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction Without Obvious Biliary Dilatation. J Pediatr Surg 2024;59:653-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sundaram S, Kale AP, Giri S, et al. Anomalous Pancreatobiliary Ductal Union Presenting as Recurrent Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis in Children and Adolescents With Response to Endotherapy. Cureus 2023;15:e35046. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ariga H, Kashimura J, Honda Y, et al. Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction with Repeated Pancreatitis Due to Protein Plugs in a Short Period. Intern Med 2024;63:2407-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Samavedy R, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic therapy in anomalous pancreatobiliary duct junction. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:623-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng JW, Kong CK, Book KS, et al. Pancreatitis and anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system in childhood. J Pediatr Surg 1993;28:1523-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng WT, Wong MK, Chan YT, et al. Clinical application of the study on sphincter of Oddi motor activity in patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction. Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:926-7. [PubMed]

- Choi BH, Lim YJ, Yoon CH, et al. Acute pancreatitis associated with biliary disease in children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;18:915-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imazu M, Iwai N, Tokiwa K, et al. Factors of biliary carcinogenesis in choledochal cysts. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2001;11:24-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Cong Y, Tan J, Zhao K, Ren K, Mao Q, Song Y, Jin Y, Cao B, Wei H. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM)-associated pancreatitis: a case report and a new treatment strategy proposed for PBM. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025;10:35.