An unusual and challenging cause of small bowel bleeding: Isolated gastrointestinal blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome

Introduction

Small bowel bleeding especially involving jejunum and ileum can be a challenging situation for any gastroenterologist. Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) are usual culprits with other potential causes including tumors and diverticulitis. Phlebectasias may be seen in the small bowel on capsule endoscopy and are difficult to differentiate from true venous malformations, as seen in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS). A high index of suspicion can expedite diagnosis and management.

BRBNS is a rare disease characterized by the appearance of blue compressible venous malformations on the skin and viscera (1). It is an autosomal dominant condition with linkage to a locus on chromosome 9p (2-4). BRBNS usually presents in childhood (5) and is rare in African Americans (AA) (6). We present an unusual and challenging case of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding that was limited to the small bowel and consistent with BRBNS.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old AA male presented to our hospital with multiple episodes of dark red stool and acute on chronic anemia. Past medical history was significant for coronary artery disease, esophageal strictures requiring multiple dilations, and hemorrhoids. Physical examination was unremarkable, and the patient was hemodynamically stable. Initial hematocrit was 18.5%, from a baseline of 25.7%. In the emergency department, he received packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and underwent CT angiography of abdomen and pelvis, which did not reveal any active bleeding.

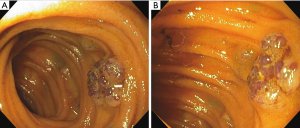

Upper endoscopy was performed which was normal, followed by colonoscopy, which showed dark red blood throughout the colon to the terminal ileum with no identifiable source of bleeding ascertained. Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) was then performed, which showed active bleeding in the proximal ileum from suspected bleeding AVMs. Single balloon enteroscopy revealed multiple (>20) non-bleeding polypoid mucosal nodules with vascular ectasia approximately 5 to 10 mm in size beginning in the proximal jejunum (Figure 1, Video 1); however, no active bleeding was appreciated. Biopsy obtained from one lesion showed normal small bowel mucosa with Peyer’s patch.

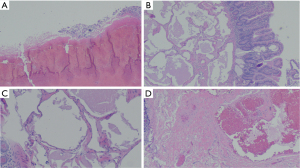

The patient continued to have persistent melena and anemia, requiring transfusion of 10 units of PRBCs throughout his hospitalization. Therefore, general surgery was consulted and an exploratory laparotomy with intraoperative enteroscopy was performed (Video 2). Multiple vascular lesions were noted in the jejunum, spanning an area of approximately 120 cm, which were consistent with BRBNS. One lesion was actively bleeding. The lesions were deemed too numerous for glue injection, and the patient therefore underwent resection of 130 cm of small bowel with subsequent re-anastomosis. Pathology of the small bowel showed marked submucosal dilated vascular structures and congestion with focal epithelial erosions, prominent submucosal vessels, and otherwise benign mucosa throughout (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the patient continued to improve clinically and had no further bleeding. He was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Four months later, he was seen in clinic where he reported normal brown stools with improved hematocrit on labs.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Bleeding from the small intestine accounts for 5–10% of all GI bleeding (7). Etiologies include vascular, inflammatory (Crohn’s disease, Behcet’s disease, intestinal tuberculosis), iatrogenic (NSAIDs, radiation, procedure related), diverticular (Meckel’s), or mass lesions (tumors, lymphomas, polyps) (8). Vascular anomalies can be further categorized into two groups: vascular malformations and vascular neoplasms (9). Vascular malformations include slow-flow malformations (venous, capillary, and lymphatic components) and fast-flow malformations (arterial component) (10). BRBNS is a slow-flow vascular malformation.

BRBNS usually presents as cutaneous lesions which most often occur on the face, trunk and limbs at birth or during early childhood (11). Along with skin manifestations, the GI tract is the most common organ system affected by BRBNS (particularly the small bowel and colon) (12) but any organ may be affected (6). The most common clinical presentation from GI involvement is acute or chronic bleeding that may result in iron deficiency anemia (6).

Evaluation of GI lesions of BRBNS include VCE, deep enteroscopy, and radiography, of which VCE is considered first-line (7). Angiography is useful in locating an actively bleeding site. Tagged red blood cell nuclear scans may show pooling of the radionuclide contrast within the venous malformations (13). Endoscopy may reveal bluish intestinal nodules with normal mucosal walls. Diagnosis of BRBNS is made clinically by the pathognomonic cutaneous lesions, endoscopic appearance of the GI lesions and histology with groups of dilated capillary structures lined by a thin layer of epidermis (11,14).

BRBNS without cutaneous manifestations is extremely rare with very few case reports published. A retrospective analysis of 120 BRBNS cases reported manifestation of the disease without skin involvement in 7% of cases (15). Fishman et al. reported ten patients who were surgically treated for BRBNS out of which one patient had no venous malformations of the skin (16). Robertson et al. described a young girl with BRBNS manifestations of paraspinal hemangioma at birth followed by venous malformations in the distal small bowel and proximal sigmoid colon but no cutaneous manifestations (17). Goud et al. reported a case of adult-onset BRBNS involving the esophagus and colon but no cutaneous manifestations (18).

The choice of treatment modalities for GI lesions depends on number of lesions, location, and size. Most patients require lifelong iron replacement and blood transfusions. Endoscopic interventions, such as band ligation, laser ablation, sclerotherapy, glue injection, surgical excision, and photocoagulation may be used to control GI bleeding. Medications such as such as propranolol, octreotide, corticosteroids, interferon alpha, thalidomide, antifibrinolytics, and sirolimus have been reported to control symptoms (19). Bowel resection is reserved for patients with a recurrent need for PRBCs. Long-term follow-up with CT and endoscopy may be necessary. If AVMs in the GI tract recur, treatment is aimed at maximal preservation of the GI tract, with medical management preferred over surgery (20). In our patient, surgical resection was necessitated due to the multiple polypoid mucosal lesions of BRBNS requiring numerous blood transfusions.

Our case describes a unique scenario of adult-onset BRBNS limited to the GI tract in an AA patient, which is rare overall in the BRBNS patient population. This highlights the point that BRBNS should be considered in patients with obscure or overt GI bleeding, even in the absence of cutaneous manifestations.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tgh.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tgh.2020.02.19/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ogu UO, Abusin G, Abu-Arja RF, et al. Successful Management of Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome (BRBNS) with Sirolimus. Case Rep Pediatr 2018;2018:7654278. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallione CJ, Pasyk KA, Boon LM, et al. A gene for familial venous malformations maps to chromosome 9p in a second large kindred. J Med Genet 1995;32:197-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walshe MM, Evans CD, Warin RP. Blue rubber bleb naevus. Br Med J 1966;2:931-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munkvad M. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Dermatologica 1983;167:307-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salloum R, Fox CE, Alvarez-Allende CR, et al. Response of Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome to Sirolimus Treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:1911-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues D. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Revista do Hospital das Clínicas 2000;55:29-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerson LB, Fidler JL, Cave DR, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1265-87; quiz 88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murphy B, Winter DC, Kavanagh DO. Small Bowel Gastrointestinal Bleeding Diagnosis and Management—A Narrative Review. Front Surg 2019;6:25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Routine aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer: recommendation statement. Am Fam Physician 2007;76:109-13. [PubMed]

- Kollipara R, Dinneen L, Rentas KE, et al. Current Classification and Terminology of Pediatric Vascular Anomalies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201:1124-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nahm WK, Moise S, Eichenfield LF, et al. Venous malformations in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: variable onset of presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:S101-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jennings M, Ward P, Maddocks JL. Blue rubber bleb naevus disease: an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Gut 1988;29:1408-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kassarjian A, Fishman SJ, Fox VL, et al. Imaging Characteristics of Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1041-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lybecker MB, Stawowy M, Clausen N. Blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome: a rare cause of chronic occult blood loss and iron deficiency anaemia. BMJ case reports 2016; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jin XL, Wang ZH, Xiao XB, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:17254-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fishman SJ, Smithers CJ, Folkman J, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: surgical eradication of gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Surg 2005;241:523-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robertson JO, Vogel AM, Kung VL, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome without cutaneous manifestations: A rare presentation of chronic anemia. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2014;2:70-2. [Crossref]

- Goud A, Abdelqader A, Walters J, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: a rare presentation of late-onset anemia and lower gastrointestinal bleeding without cutaneous manifestations. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2016;6:29966. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuksekkaya H, Ozbek O, Keser M, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: successful treatment with sirolimus. Pediatrics-English Edition 2012;129:e1080.

- Nakajima H, Nouso H, Urushihara N, et al. Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome with Long-Term Follow-Up: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2018;2018:8087659. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Reddy YK, Bayoumi M, Barnes M, Gillespie W, Kamal F, Ismail M, Bilal M. An unusual and challenging cause of small bowel bleeding: Isolated gastrointestinal blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:12.